I had already started this post prior to my husband Patrick falling during a trail run and fracturing his rib. And with that turn of events, the topic has taken even more meaning: I was in the midst of contemplating the power of two (or more) to create an outcome better than the sum of its parts, both in the division of labor (people), and in the progression of ideas.

The question, as cliché as it might be: “Are we all on the same sheet of music?” is a good question in fact, because when we are, we become more than a room full of people playing instruments, we create a symphony.

Division of Labor

Which takes me back to Patrick’s accident. He’s fine; we were lucky. However, at about 50 percent of his productivity level, I have become more aware of the importance of the division of labor in our own household – it’s something most of us take for granted when it runs smoothly – like the internet (Hey! did you hear? We don’t have to capitalize internet anymore!) and the faucet in your kitchen. When it doesn’t work, life as we know it shifts.

For example, I can’t cook. This family would die if we relied on my cooking. That’s Patrick’s role. Likewise, he’s not great at grammar and spelling, so he sends important correspondence through me. This is how tribes survive; how companies thrive. We rely on the strengths of everyone involved. No one does it alone.

There is power in two (or more).

In The Rational Optimist, Matt Ridley explains that specialization and the division of labor is what has helped civilization advance. Individuals work on getting really good at the thing they are working on. While someone was out chasing food, someone else was back at the basecamp figuring out how to make a spearhead to better catch food, something he/she couldn’t have done if the other person wasn’t out catching food so they could nourish themselves in the meantime.

Now that you and I can replace hunting and gathering with a stop at the market on the way home from work, thanks to the people before us who sorted out better processes for us, we have more time available to us to create new ideas.

Progression of Ideas

This is how ideas progress. And if we look at the rate of progression, say, since the beginning of time, we’ll see the increase is exponential. Take a two-decade sample back in 3000 (2990 – 3000) BC vs. the time frame of 1995 – 2015. Rate of change is much higher. We have a definite advantage now given the tools we have vs. the tools we had to work with in 3000 years BC. It’s kind of like being on the inside lane in the track.

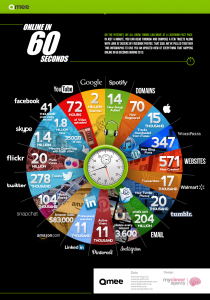

Let’s look at some stats. This infographic shows what happens in a minute on the internet in 2013. (We could reasonably consider this ancient because it’s three years old) Between 2012 and 2013, the number of emails increased by 36 million per minute.

PER MINUTE. 347 new WordPress blog posts per minute.

According to The Atlantic, there were fewer than 3,000 websites in 1994. That number is expected to exceed 3 billion by 2016. Considering how a large percentage of these websites have changed the way each of us conduct our daily lives and businesses, this represents significant change.

How Do You Compete With That?

One might argue there are no more ideas left so how can we continue to innovate?

The power of numbers applies equally to ideas as it does to people.

The other day, a colleague and I were chatting about this. She said she wanted to be known for a particular topic but that it wasn’t possible someone else is already known for it. What second or third idea can you introduce that makes it a different angle? How does her experience or background inform this topic differently than the other person she referenced? Even more importantly, how can she do it better?

Look no further than Uber as an example. Uber came onto the market in 2010 as a new idea solving a specific problem in the transportation industry. It provided drivers with new opportunities and passengers with a user experience that was widely loved – contributing to massive growth for Uber. It has since been plagued with regulatory, safety, and leadership problems. Juno thinks it can do Uber better, not by copying the idea, but by taking it, seeing the weaknesses and doing it differently. By learning from Uber, it can progress this idea to an improved one.

Being first to market doesn’t necessarily win if you can come in and do it better. Progression of ideas.

Every Oscar acceptance speech starts with “I’d like to thank…” and there’s a reason for that.

None of us would be where we are today without the people in our lives now, and without the people and their ideas who came before us. Success doesn’t happen in a vacuum. We can stop taking it for granted – I know I will even with something as simple as a fractured rib.

Interested in elevating your organization’s positioning with effective storytelling?

Download this ebook: From Transactional to Transformational

[ssba]

This is a wonderful post. I admire the depth including both personal anecdote and anthropology. I do have one simple answer to 3 billion websites: show up consistently every day and do your best. It’s a simple answer, not an easy one.

It does take perseverance, doesn’t it? Everyone has 18 better thing they could be doing at any given moment.

Having said said that, thanks for using a few here, Frank. 🙂